Two times a week I go to a room full of people whose chief concerns regard the nature of time, consciousness, the mind, the body, and the presuppositions that ground our beliefs in the existence of all these aforementioned items. Most of the time we talk about capitalism and decide nothing is worth trying until a revolution. I get really tired, really fast, and think about how much more energy we might invest in semantics before we get to write something that does something beyond deconstruction and destabilization. It feels like there is nothing new to discover, only pasts that get more problematic the more you learn about them.

And yet. People walk out of class with their minds alight, feverish over ideas they haven't heard-or that have been suppressed-in their home countries. Sophie finds purpose in Hegel's struggle for recognition. She is trans. For her the moment of meeting, of constituting herself as a subject--woman-- is a fight to the death, just as Hegel describes it. She must avoid objectification narrowly: through her, the dialectic becomes alive. For Theresa and Ana-Lucia, who come from Latin America, the notion that we perform gender sets their nerves on fire. They can finally see what is, after all, not inherent. They think of their mothers and grandmothers who teach them the ways of the kitchen, who teach them to wear their hair long and swear quietly or not at all. I am proud and sometimes touched for them, holding their hands as they tell me about their pasts, as they quote our readings back to me. It is empowering to watch, and to feel. But all the while I crave a revelation of my own.This month has been fast and slow at the same time. I am lucky to have traveled extensively and hosted friends and family, and I am somewhat less lucky to have battled a nasty sinus infection and several bad cases of malfunctioning technology. Every moment where good things happen feels destined and preordained, and every minute something goes wrong I feel lost at sea and heartbroken. There is an argument here for tempering my own reactions to stimuli, for remaining coolly detached from my changing circumstances and increasingly complex lifestyle here, but if this ability has been neatly described somewhere, I missed it.

I have a presentation next week on Hannah Arendt's The Human Condition. In the fifth chapter she lays out her theory of action and how we come to constitute ourselves as political subjects. In some ways for Arendt our entrance into the world comes at the unity of speech and action, a "second birth" in which we announce who we are to the public realm, and insert ourselves into the web of human relationships. Public action, public speech, and the disclosure of identity such activities provide constitute our interrelationships and interdependence--that is, our words and deeds literally create our social realities. The point of this is that our experience of the world is fundamentally intersubjective, and so too (Arendt will argue) are our politics. An interesting side effect of this theory is that storytelling and narrative become the only means by which humankind can continue on, generation after generation. Action and speech are fleeting; we need something to take them up, to fashion a story that lives even after we die. It is a really basic principle, and it means that we can never be the authors of our own stories. We need observers, authors, and makers, in addition to actions and their agents. This is why, famously, history for Arendt is always a "backwards glance." We tell ourselves stories in order to live, Arendt says. The problem with being the agent in a given story, though, is that you have no idea how things are going to turn out. We don't know what is happening while it is happening, don't understand its arc or internal logic or if the ending will make sense. To me this is messy and awkward, and I find myself thinking about it more these days than I ever have. I don't know if this is a symptom of moving, or simply of being young and relatively unencumbered by responsibility. I'm adrift in a web of my own actions, and I watch the implications play out with no clue how they will reverberate.

I asked my friend Gloria from school if she feels the same psychic fears about this as I do, if she too craves a revelation, an epiphany, a flash of recognition that proves that everything we are doing now will play out the way we hope it will someday soon. There is no room for private stories in the kingdom of Arendt, I say, and apparently this criticism is the same as the ones made by feminists over the years (although I assume for different reasons). Gloria doesn't really experience the same urgency about life as I do. She is Italian and knows a great deal more about things, like rolling her own cigarettes and reading philosophy. This kind of person doesn't need revelations around which to structure their young life, because they have the magical gift of trusting themselves (annoying, having friends like that). We've only known each other for a month but I actually can't remember how we met. One day she must've introduced herself to me and said "I'm Gloria," and a certain point she bought a muffin and we picked at it together outside, daring the seagulls to attack. It is easy to speak freely about myself to her. I can't explain it, except to say that moving springs something loose in you that sweeps away all the pretentious debris gathering in little corners around your mind. Gloria's magic is that she listens the way she speaks, with economy and honesty. Maybe this is because English is not her first language, so she has fewer words to choose from. Their impact is greater. In contrast to her I feel like my language is so enormous, inflated with nothingness. I try not to feel like this blank, shimmering thing on her arm when we walk around, as if I can absorb her cool.

I'm still a little unclear on the details, but Talia met a bunch of young Catholics in a coffee shop one day and they all got on great. A few days later I found myself at a bonfire with a mixed crowd--some expats, some Irish--making a strange combination of s'mores with Cadbury chocolate and Digestive biscuits. Most everyone there worked or was involved in the nearby ministry.

"If you guys want, there's going to be a fun Mass on Sunday," One of them had said, rolling her eyes like she knew how ridiculous it sounded. Maybe that's how I sounded every time I had invited someone to come to Hillel, self-deprecating but still glowing with the knowledge that no, actually, it would be fun if you could be bothered to show up. "You can all come, you don’t have to be…well, you know." I smiled at her because I didn’t want her to think she offended me when she hadn't.

I've always had a strange view of religious Christians, as if there was no middle ground between being secular and being out to get me, or convert me, or both. I passed beers around the semicircle of people gathered around the fire and had to remind myself that the people I was having fun with were genuinely normal people. That is the strange thing about living in a religious country: piety comes cheaper, here. If being part of things like the Church or youth groups or bible study is commonplace in your country, you don't have to sacrifice normal things like drinking beer and listening to folk music and making s'mores on a Friday night to be religious. Setting aside the Irish people in the group, so many of them had come to find their own version of revelation, and had found community in doing so. I was a little jealous watching them, at the straightforwardness of it all. Even though I'm not Catholic, I still feel Ireland is a good place for me to convene with the ancient and the spiritual. Life here is laden with mythicism, ranging from the charming--like the babbling brooks and fairy pools of Wicklow--to the sublime--the golden inscriptions of the ancient Book of Kells, genuinely gleaming, even after thousands of years. I went to Galway excited to explore this particular aspect of living in Ireland, what I'd imagined when I'd submitted an application eons ago: fueled by the fantasy of an ancient past and a precarious future, I'd write some fabulous dissertation and maybe other things too, finding inspiration like the Celts of old. It sounds dumber writing it down, but it's true.

On the morning we left I drank coffee so hot I burned my tongue. My grey day bag was open on the floor of my bedroom, the blue carpet no longer registering in my field of perception (thank goodness). I crouched over it, throwing in clothes, shoes, two pairs of pants in different (imperceptible) shades of denim, a few shirts to go dancing and hiking in, depending on the nature of the weekend. This was more than I would need for the trip. Although we weren't late I was still in a hurry. It didn't matter if I separated the clothes from my shoes or my toiletries. I was so eager to get on the train, I wanted everything zipped and closed and prepared before noon. I needed to get on the road, watch the train roll by miles and miles of indistinguishable green countryside to help me clear my head. We spent the first few days watching people on streets that by then were familiar to me. By the end of the night watching Clio's reactions to everything had me thinking that I'd settled far more deeply into the pace of life here than I thought I had, that the trad sessions and all the dancing and drinking didn't really register as novel anymore, though I still found it charming. The next day we went hiking after a rather laborious search for the correct bus.

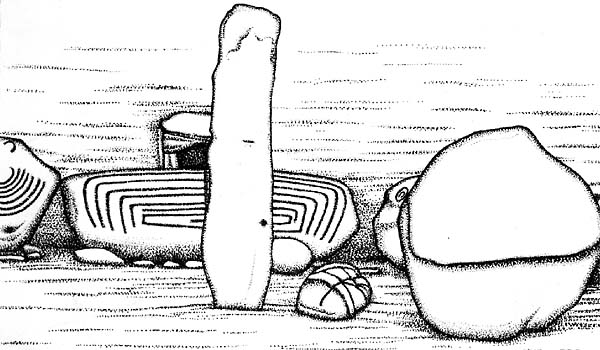

Connemara National Park is on the edge of Ireland's West Coast. The jagged edge of the land mass cuts down into the Atlantic sharply, like cut glass. The wind, howling, nearly pushed me over as we climbed. I had to use my hands and feet at some point, and touching the rocks with my palms--which had gotten soft with nearly a month of nonuse, at the gym or elsewhere--made me feel like I was on some real adventure. Near the middle of the hike, before its most strenuous leg, there's a large stone surrounded in a circle of smaller stones. Grass in yellows and greens grows beneath it. In Ireland these standing stones and the earthen mounds they rest on are usually nothing to write home about--there are so many surrounded by trails and castles and sheep. This one was nonchalant too; we only spent a few moments circling around it, trying to see what the fuss was about. The plaque told me that it was very very old, that historians could only imagine the kinds of people who had placed it there. It reminded me of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, of that whole monolith sequence in the first part of the movie. Why is everyone in this country, I thought, attracted to these great flat slabs? As a recent arrival to Ireland I guess I hadn't spent enough time thinking about the fact that revelation could be culturally specific. From my own standpoint I felt this promiscuous mix of the ancient with the mundane to be interesting but not transcendent, and so I looked at this megalithic stone and thought it was not particularly curious nor distinctive. But my own standards are skewed, maybe by my own aesthetic sensibilities or maybe because Americans aren't taught to see the magic and the myth in the natural world and its histories. I'm trying to look deeper. I read a little book about these large stones that I see everywhere, and as it turns out the Irish people have sayings and stories about them. Some believe they were cast down by giants, thrown into fields as expressions of love or rage or both. Some stones have rock crystals growing one side, or don't sit exactly straight. These things are significant and meaningful. People have favorites. There is one called the "Hurlstone" which inspired a series of paintings, which has a diagonal north-south setting in a field with a compass reading through the aperture of 175 degrees south. If you follow its' diagonal line and climb over the hills, it leads you straight to Knowth--the largest and earliest of three enormous passage grave Earth mounds on the River Boyne. This is pretty cool, and I wouldn'st have even thought to look into it, because I think rocks are boring. All this is to say inspiration and revelation and purpose are not handed to you. I am learning how to configure things to be plump with portents, to make meaning even where I cannot find it at first. I think it is a worthy enterprise.