Somewhere between the time when you are meant to be working on finals and when we actually began to be worried about them, Gloria and I took a trip to Edinburgh. As it turned out, I should have been worried about them then, but Dublin had begun to look bleak and weary as the winter droned on and I wanted to find someplace with winter cheer. The birches had long since shivered off their coats and the sea, usually garrulous, was flat and grey like a stone. I knew better than to long for something that wasn't coming--a bit of open road, sunlight honeying the landscape--but I figured some new scenery would help me romanticize a season with which I had long since accepted defeat.

We arrived a little past midnight. The air was colder than anything I had felt for a while--we would watch over the next few days as it turned to snow, the white puffs sticking brazenly in my hair, as if they belonged. We walked fast, not wanting to be on the streets for too long in the frigid air with our stuffed backpacks, but I do find myself wishing we had slowed down. It would be the last time I saw the streets this empty, had the long winding passageways and dark cobblestones all to myself.

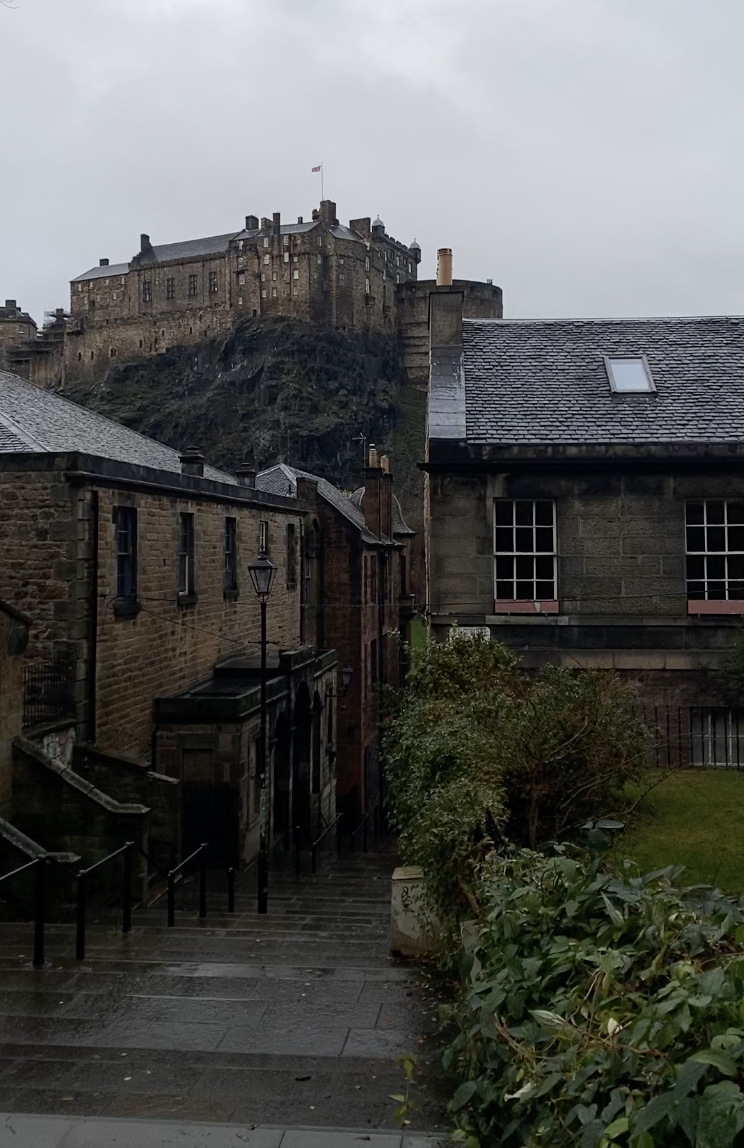

The first thing I noticed about the city--besides the crowds and the bitter cold air--was the unity. Everything beneath the watchful eye of the castle seemed to fit together, all grey flagstone and gothic archways and gas lamps, flickering somewhere between orange and red. The only telltale signs of refurbishment were the very many espresso machines peering out of windows, alien-like and misplaced.

After the typical due diligence at the cathedrals, we walked to the castle. It looked as if it was etched from the very stone of the mountain, something inevitable in its posture. From the ground level you can see it from nearly everywhere, though the views are best from the coffee shops and bookstores on the far side of the old city, closer to the university campus. I wondered how long I'd have to live there before its signification faded, becoming a mere orientating device. Gloria tells me the Coliseum in Rome functions the same way, a convenient meeting spot for university students. You could have dinner in one of the streets bounded by the massive Roman stadium and the Via Celio Vibenna, or you could have dinner on the other side, by the Piazza del Colosseo. Most of her friends have never been inside, hounded as they are by the exorbitant ticket prices and the throngs of tourists. I tried to think of an equivalent, but no one I know has ever met up by the Hollywood sign, or had dinner under the watchful eye of the giant, inflatable minion overlooking the East Valley. I tried to bring up how rare that is, to have something so ancient and inevitable in the beating heart of the city, but I was beginning to see how it isn't rare at all--only for me. And even now I was desensitized to it, I thought, as we did a loop around the castle and decided against paying the entrance fee to go inside.

In the evening we milled around a Christmas market, clutching paper cups of mulled cider and and shivering in the gentle, inexorable snow. At some point we handed someone cash to strap us (loosely) into a 400 foot tall swing. Colloquially the machine is known as a Sky-screamer and from my point of view this is very apt. We did three or four loops in the freezing air, held in place by a metal swing seat and one very measly looking piece of chainlink. We flew over the Scott monument, which I learned afterwards is the largest monument to a writer in the world. Each time we went around, its tip glinted in the strange Carnaval lights shining from below.

We walked about forty minutes outside the old city, trying to see something of where people might actually live and work and walk their dogs. While these areas were significantly less cobblestone-y, and therefore less mystical than they might have otherwise appeared to me, I was still struck by how very few odds and ends there were scattered through the very respectable streets. This gives the city the unique quality of deep aesthetic congruity, so deep that I found myself succumbing to the city's charms--a hidden archway here, a weeping willow just barely skimming the surface of a pond there. By the time we found the Village of Dean, took in the strangely stucco-looking apartment buildings, and had a smoke in some destitute playground, I was charmed so thoroughly that I was no longer a good judge of the city's character. I remembered something I had read in Stockholm months ago, at the Peter Lindbergh exhibit. He said that you had to fall in love with the subject in order to photograph it. I didn't see how that could be very difficult for Mr. Lindbergh who mostly photographed models and actresses for Vogue. People like that are probably very easy to fall in love with--striking, magnetic people, whose job is to cut right to the very heart of aesthetics and grip you, even when you're full of derision for surface-level beauty and design. I wondered if his advice applied to cities and to writers. I had left space in my backpack because I knew I would want to buy a few books that in some way would remind me of the city, perhaps very literally or even obliquely, by being written by an author who lived in Edinburgh. Would such writers be very good at writing about Edinburgh, if they lived there and loved it? I loved it already, I could tell, but in a Lindberghian way--I was infatuated with it, lusting after it, even. I wanted to inscribe the particular contours of the streets and the buildings onto the page so I could study it over and over, and I didn't dare fashion a critique, a real sense of its social stratification, its deep political conflicts, its erstwhile colonial history. That bodes for some very boring writing, if only because it is so shallow. The kind of love that you need to write about something is truthfully very different, the kind that comes from the intimacy of knowing all of its good and bad, a thicker and untranscendent love, like that of an old friend whose behavior is so predictable as to be laughable.

Later, at a place called Armchair books, I picked up a little novel that had been serialized in a daily newspaper for some time. For a few pounds more the shop-owner offered to give me a canvas bag with the bookstore logo emblazoned on the front. After I accepted his offer he said something like "Capitalism always wins," and I wondered if he had meant to sound like he was judging me for acquiescing to what seemed like a good deal, or if he was angry at himself for having to make such an offer in the first place. I made some comment back to him, trying to sound like I too was some kind of consumer cynic and had long since accepted the limits of ethical consumption under capitalism, which opened up something like a conversation.

All the perfunctory remarks went on without a hitch, after which I seemed to have his approval despite the capitalism comment."You have to lead your own life," He said, sounding sure. "That's what a gap year is for."

"Exactly," I replied. "A gap year is..."

I faltered. I wasn't at all sure what a gap year was really for. Was it a time during which one was supposed to grow up, somehow? Was it an expensive indulgence, a holiday in all but name? The people in my classes didn't seem to think so, but then again, all of them need the degree to start teaching (except the girl from Utah who pulled me aside during our feminist and gender theory class and told me in a hushed voice that she was heading back home to get married, of all things, at the end of the year. It seemed to me like I was one of the only ones in the program who would interpret this news the way she meant it--a happy ending, rather than another tale of patriarchal victimization.) I wanted to say it was a "rite de passage" for somewhat educated kids of the upper middle class, but I didn't want to sound rude, or like I had done all this schooling and come out the other side convinced that more education wasn't really a virtue.

He changed the subject and I left soon after, taking the tote bag with me. I had picked up some of his anxieties during the conversation, it seemed, and was glad to be out of the shop and in the street. Before long it started to rain again, and we headed to the National Museum of Scotland. It was more of a menagerie than a museum, featuring full diorama-like reconstructions of various scenes in Scotland's natural history, some hallways full of ancient objects and a sarcophagus, possibly on loan from the British museum's Collection of Stolen Stuff, random art from everywhere, it seemed like, including a very odd section on indigenous art from California and other Western states that made me strangely homesick, and lots of exhibits on various technological innovations like the steam engine and space rockets. The connection to Scotland was emphasized most vigorously in the natural history sections, which advertised themselves as telling the "story" of Scotland beginning with the Proterozoic eon, during which the oldest rocks of Scotland--Lewiston gneisses--were formed in the Outer Hebrides. There was something funny about the tinny VHS tapes that played looped animations of plate tectonic movement, all of which were labelled with the present-day borders: Scotland, Wales, Iceland. As if they predated everything.

And yet as we moved through the borders seemed to matter less and less--an Egyptian mummy, Serbian electric engineering, and American space shuttles all took their rightful place in the annals of Scottish national history. The building was so large and so utterly incongruous that after two hours of walking we both called it quits in unison.

At the museum cafe I read the first installment of the book I had purchased. I recognized that its point was to delight in the various quirks and eccentricities that the author had managed to recollect from much people-watching in the city. I played a kind of bingo with myself, hoping to see some of the buildings and perhaps even the strange people that had inspired him. I didn't find much, but then again, I'm not very observant. I looked up the novel in my bunk bed later and read that it was the longest serialized novel in the entire world, which makes sense, as there are currently 17 books to the series and counting. 17 books, released chapter by chapter, in one newspaper, and then gently assembled into something resembling a series. Were there really 17 books-worth of things to say about Edinburgh's New Town? I wasn't so sure.